- Home

- Aimen Dean

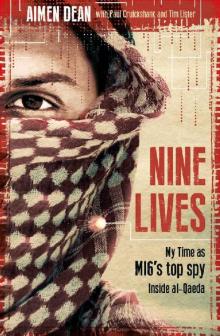

Nine Lives: My time as the West's top spy inside al-Qaeda Page 2

Nine Lives: My time as the West's top spy inside al-Qaeda Read online

Page 2

My poor mother endured a barrage of interrogation. Who was the bearded man everyone was afraid of in Iran? Why were the Persians bad? When she was exhausted I would turn my fire on my brothers, who would not hesitate to reinforce my budding Sunni identity. To grow up amid such upheaval was extraordinarily formative, an early and very real introduction to the political and religious rifts that would dominate my life.

Not that Khobar had yet been touched by this turbulence. It was comfortable and ordered in the 1980s; change did not come to Saudi Arabia quickly. Our Muslim identity may have been very conservative socially, but it was also utterly quiescent. Political agitation was unthinkable, which made the Durranis rather unusual.

Every week we would gather round the dining table after Friday prayers – six brothers and their mother. Invariably it was politics for the main course and theology for dessert. I was soon aware of the noble struggle in Afghanistan against the Russians, of the call to jihad* that had lured thousands of Arabs to the foothills of the Himalayas. There was much talk of a neighbour who had gone to fight.

In this age of video games, social media, countless TV channels, texting and apps, it may seem odd that just one generation ago a child could have become steeped in Islamic literature. But that was me: I was attending an Islamic study circle at the Omar bin Abdelaziz mosque by the age of nine, helping in a local Islamic bookshop by the age of eleven, and thanks to a photographic memory knew the Koran by heart at the age of twelve.** I found the mosque enthralling in the traditional sense of the word. Its minarets reached towards God; the latticed arches and acres of plush blue-gold carpet instilled in me a sense of awe. Besides the Koran, I was particularly enchanted by large leather-bound collections of hadith* and fascinated by the mysterious prophecies these collections contained.**

On 2 August 1990, just a month before my twelfth birthday, Saddam Hussein’s army invaded Kuwait. The man who had won support in the Arab world for going to war with the Shia theocracy in Iran had turned his vast army on his fellow Sunnis. Khobar was just down the coast from Kuwait; for a few fevered days we expected Iraqi tanks to roll south into the rich oilfields of the Eastern Province. People stocked up on supplies, made sure their vehicles were fuelled, even bought gas masks – just in case.

Kuwaiti refugees – perhaps the most affluent exodus in history – arrived in their limousines and 4x4s, laden down with whatever valuables they had been able to grab before fleeing. And then US forces arrived – the infidel come to guard the Custodians of the Two Holy Mosques from a secular dictator who had just declared himself the true adherent of Islam. The world was upside down. But to me the American presence offered reassurance, a sense that Saddam (whom we had vocally supported against Iran) would be stopped and turned back. We had heard much – some of it no doubt apocryphal – of the looting and atrocities visited upon Kuwait by his troops.

The American soldiers in their desert fatigues went to fast-food restaurants around Khobar and manned their discreetly placed anti-missile batteries to deter the Iraqis’ dreaded Scuds. I saw several of Saddam’s missiles arcing towards Saudi territory before they were taken out in mid-air. The Americans all seemed so much bigger and more muscular than the average Saudi, with a swashbuckling confidence and faith in technology that was so alien to our culture.

The government went to great lengths to persuade Saudis of the ‘blessings of safety and security’ – but others more worldly than me knew it was a charade. Without the Americans, we would have been hard put to resist Saddam’s huge army, even if it was still recovering from a decade of conflict with Iran. The invasion of Kuwait brought war, politics and religion into everyday conversation. For a twelve-year-old already steeped in the region’s turmoil, it was like attending finishing school.

Then, in the summer of 1991, just before I turned thirteen, my mother died of a brain aneurism. I was inconsolable. I had become the centre of her world as my brothers had grown into teenagers and young men. She was a spiritual person and wanted me to be pious, perhaps to become an imam. She was very proud of my mastery of the Koran and had encouraged my religious studies, getting my brothers to introduce me to prominent religious figures in Khobar.

When I lost my mother I lost a teacher, mentor and companion. I eventually found companionship and solace in an unlikely place: the six volumes and 4,000 pages of Sayyid Qutb’s In the Shade of the Koran.

Qutb, the founding father of modern jihad and of a radical and profound interpretation of Islam, had written the book in times of pain and hardship, when he had been tortured in Egyptian jails in the 1950s and 1960s. I related to the suffering as much as the scholarship and the beauty of his writing. It took me two years to finish his masterwork. But it made a deep impression on me.

I was drawn to his explanations of God’s sovereignty over creation, and his argument that most Muslims, corrupted by Western modernity and secularism, had lost sight of the divine. We had been plunged back into an age of jahiliyah (pre-Islamic ignorance). He made a defiant call, over the heads of the grand clerics and scholars of Islam, for the restoration of God’s Kingdom on Earth. His words about the state of the Muslim world and why change should come, even by violent means, were persuasive to me. God’s law was supreme over man-made laws.

Qutb’s central and revolutionary premise was that you cannot preach your way into power, for those who possess power possess the means of violence. If you shy away from wresting power from them by violence then you are doomed to failure.

His arguments were purgative to a teenager brought up in the sluggish complacency of Saudi Arabia. Even as I read Qutb’s works, the real world was validating his philosophy. In December 1991, the Islamist party in Algeria – the FIS – won the first round of parliamentary elections. The Algerian army immediately staged a coup and put FIS party leaders in prison or sent them into exile.

Despite his radical challenge to the Islamic establishment, Qutb’s writing was inexplicably tolerated by the Saudi establishment in the early 1990s. We frequently discussed it in a study group – the Islamic Awareness Circle – that I attended at the Omar bin Abdelaziz mosque. I was admitted to the group when I was nine after passing a general knowledge test designed for thirteen-year-olds. Those Friday lunches had been a good education.

The Circle was like a Scout troop but with religious underpinnings. We were as interested in camping trips and barbecues as we were in theological debate and current affairs. The ‘rock children’ of the Palestinian territories were our heroes. In those days the Palestinian cause was still dear to the hearts of young Arabs all over the Middle East, before it was overshadowed and then submerged by the greater struggle for the soul of our religion.

The Circle included individuals who would shape both my future and the emergence of Islamist militancy in Saudi Arabia. One instructor who visited from time to time was a lanky university student called Yusuf al-Ayeri. He had sunken eyes and a strong jaw that made him slightly forbidding, as did his intense and humourless demeanour. I cannot recall seeing him smile, let alone laugh.

Born into an upper-middle-class family in Dammam,* al-Ayeri told us that he had fought in Afghanistan against the Communists before coming back home to pursue Shariah studies. He had taken the writings of Sayyid Qutb very much to heart, constantly nagging the Circle about how Western culture was corrupting Muslim societies. He alleged, for example, that the patties at the Saudi franchise of the American burger chain Hardee’s were made from pork. With a straight face, he told us that Pepsi stood for ‘Pay Every Penny to Save Israel’. And when you held a bottle of Coca-Cola to the mirror, the reflected logo in Arabic read ‘No Mohammed No Mecca’.

It was a shame as I loved Coke.

One afternoon, al-Ayeri ventured into still more absurd territory. The Circle was sitting on the carpet of the mosque’s library.

‘I have learned,’ he said gravely, ‘that some of you watch The Smurfs on television.’

The Smurfs – a cartoon series featuring blue and white anthrop

omorphous creatures living in a forest – were a global phenomenon. I looked down; it was one of my favourite shows.

‘This is haram [forbidden],’ al-Ayeri continued. ‘The Smurfs are a Western plot to destroy the fabric of our society, to destroy morality in our children and respect for their parents. If you watch this you’re going to start carrying out pranks and mixing magic potions. This is not normal; Islam forbids it.’

But he wasn’t finished.

‘There is also a lot of sexuality with the female Smurf. She dresses and behaves in a disgusting way.’

Despite al-Ayeri’s proscription, I continued to watch The Smurfs. In a way, it was my guilty secret. On the other hand, I could think of nothing in the Koran or hadith that might be applicable to The Smurfs. If it was a Western plot, I told myself, it would only seduce the most gullible.

Among my fellow students in the group was Khalid al-Hajj, who was three years my senior. Khalid had been born into a Yemeni family in Jeddah and had moved to Khobar when he was very young. Olive-skinned, tall and athletic, he had large, deep-set brown eyes that had a strangely soothing effect. His level-headed disposition was the perfect foil for my hyperactive energy and tendency to be an insufferable know-it-all. Where I saw complexity, he saw black and white. At the same time, he had a restless soul.

We would have a long, close and turbulent relationship.

While in many ways we were yin and yang, we shared a deep religious fervour and a competitive streak. Khalid led a team which competed in Islamic poetry competitions against other Islamic Circles. I was the team’s secret weapon, thanks to my memory and deep immersion in all things Islamic. I had memorized so much Arabic poetry that our team became champions of the Eastern Province. Khalid beamed when Prince Saud bin Nayef, then deputy governor of the province, presented us with the trophy.

Only once in competition was I bested. My nemesis was a young Syrian who left me lost for words after a two-hour poetry duel.

‘I want a rematch, I know I’m better than him,’ I had declared to Khalid, unfamiliar with the taste of defeat.

‘Everybody knows you are very smart, Ali,’ Khalid replied. ‘One day you are going to be a fine imam or a famous professor of Islamic history, Insha’allah. But you need to relax a little. Sometimes you remind me of our cat at home; you always need your ego stroked.’

After my mother passed away, my brothers were my guardians, while Chitrah, an endlessly patient woman from Sri Lanka who was our maid, ensured I was fed and clothed. My brothers were very different from me – into sports and martial arts – but protective of their little sibling. And I was not the most difficult of charges: diligent and quiet, more likely to be buried in a book than climbing fences or hanging out with a bad crowd.

If there was an authority figure in my life it was my eldest brother, Moheddin, eighteen years my senior, a natural athlete who was powerfully built and held a judo black belt. After graduating in chemical engineering from King Fahd University in Dhahran, Moheddin had studied in Florida and California in the early 1980s. He dreamed of dropping out and becoming a hippy, travelling around the US in a multicoloured van. But he was nearly twenty years too late. The flowers and the music had given way to the Reagan Doctrine, and the United States was confronting its enemies aggressively, whether in tiny Grenada or Gadhafi’s Libya. Moheddin was angered by what he saw as the United States’ overbearing use of military power. In a fit of frustration he had smashed his guitar, come home to Saudi Arabia and turned increasingly to religion.

By 1989, Moheddin had grown a long auburn beard and felt it his duty to respond to the call of jihad. Even though he was by then married with a son, he went to Afghanistan for three months to participate in the tail end of the war against the Communists. He had flown out with a friend who would much later become a renowned leader of jihad in Chechnya.* For a quiet town on the Gulf, Khobar was turning out more than its fair share of militants.

On his return, Moheddin told us stories about the fighting around Khost and lectured us on the duty of every able-bodied Muslim to fight in defence of Islam. But by then his priority was to look after his growing family, and he substituted the romance of jihad with a more mundane existence at the regional chamber of commerce.

Moheddin was the brother I most respected but I was closest to Omar. Relaxed and free-spirited, he wore his religion lightly. He would light up any gathering with his wisecracks. His cheerful demeanour and good looks (he might have been named Omar for Sharif) made him very popular with women, and his job at Dhahran airport meant that, unusually for a young Saudi male, he had the chance to mix with the opposite sex. There were even rumours of a clandestine romance among the check-in desks, which he denied with a cheeky smile.

At this time, my whole universe was male. Even during the famous Friday lunches, sisters-in-law and female cousins dined separately. Not once during my youth in Saudi Arabia did I see a female over the age of ten, besides my mother, who was not fully veiled. Even Moheddin’s wife wore a veil in my presence.

In the spring of 1992 the Bosnian civil war broke out. Yugoslavia was falling apart. Slovenia and Croatia had already seceded from the federation that Josip Tito had so adroitly held together for decades. Bosnia was a patchwork of Muslims, Croats and Serbs, and the conflict had kicked off when the Muslims and Croats voted for independence. It quickly consumed the evening news broadcasts in Saudi Arabia, which depicted it as a Christian crusade against defenceless Muslims, with images and descriptions of Croatian and Serb atrocities against Bosnia’s Muslims.

At that same time, my friend Khalid made a two-month trip to Afghanistan to train and fight with the mujahideen against the Communist government. He was just sixteen. Osama bin Laden had made the cause popular among young radicals; at any one time there were probably about 4,000 ‘Afghan Arabs’,2 as they came to be known, fighting or training in Afghanistan.* Many more became aid workers, teachers and medics, serving the tide of Afghan refugees that had arrived in northern Pakistan.

Khalid told me stories of battles around Jalalabad and camps in the mountains. There was no bombast in his accounts; he spoke in matter-of-fact tones about the duty of jihad.

‘All Muslims should be trained because there always might come a day when we need to pick up arms to defend the faith,’ he declared.

My study group frequently talked about the Bosnian war and those who had gone to fight – including my school maths teacher, who was killed after just a couple of months in the Balkans.* From a prominent family, his father was a brigadier in the Interior Ministry, but in those days there was pride rather than shame in having a family member leave home to wage jihad.

At a book fair I bought an audiotape about Bosnia called Drops of Tears and Blood, in which students from religious seminaries there talked about the ‘ethnic cleansing’ of Muslims, their horror stories skilfully interspersed with religious hymns sung in Turkish and Arabic. At school we were shown a documentary, The Cross Is Throwing Down a Challenge, whose message was searing and simple. There was a new Christian crusade against Islam.

We were beginning to understand that we lived in turbulent times, especially for our religion and its most puritanical strand: Salafism.**

The term is often loosely and inaccurately used but essentially there are three strands of Salafism. In the study group we scoffed at the traditional quiescent variant, which our teachers mocked as ‘royalist’ because it posed no challenge to the Saudi royal family. This was a stagnant interpretation of Islam, cloaked in robes of tribalism and heavily ritualistic, inadequate for the challenges of our times.

My friends and mentors were gravitating towards a more politically active interpretation, best exemplified by the Muslim Brotherhood’s involvement in social work and discreet political activism. This interpretation was obliquely critical of the government, but not enough to get us into any trouble. We wanted Islam to be defiant – to free Muslims from the idols of capitalism and socialism – but we also wanted it to be spared human revision

ism. As Qutb had put it: ‘[Islam] is a revolt against any human situation where sovereignty, or indeed Godhead, is given to human beings . . . As a declaration of human liberation, Islam means returning God’s authority to Him, rejecting the usurpers who rule over human communities according to man-made laws.’4

The third strand was jihadi Salafism, a more radical call to take up arms in defence of Islam, one that was gaining support as Muslims perceived a growing offensive against their faith. In time, this movement became increasingly hostile to the Western powers and the sclerotic Arab governments they protected.

In Islam, holy war is fought to defend Muslim territories and communities against a military assault, either by a non-Muslim army or by Muslim aggressors. Such defensive jihad is considered to be Fard al-Ayn, a ‘mandatory obligation’, meaning that every able-bodied man and woman should participate in the defence of their territory and community.*

A few months before my fifteenth birthday, I gathered my earnings from my part-time job in the Islamic bookshop and set off for my first trip alone to Mecca. I was still immersed in the works of Qutb and his brother Mohammed; I read them like other young idealists had read Marx and Lenin. I took Qutb’s seminal 1964 volume Milestones into the Great Mosque. Standing against one of the pillars facing the Kaabah, which hundreds of thousands of Muslims circle every year at the climax of the Hajj, I was absorbed in the book for three days.

It portrayed Islam as persecuted by the modern world, under threat from the West and secularism at a time when it was more necessary than ever for the salvation of all mankind. Only a revival of the ‘true’ religion among a Vanguard could create an Islamic movement capable of rising above and confronting those standing in the way of the spread of ‘true’ Islam. For Qutb this entailed all the existing systems of governments in the Arab world and all the secular ideologies of the twentieth century including communism. So deep and rich was the language that I read every chapter twice. I was transfixed by the message; the setting where I read the book no doubt illuminated its perspective.

Nine Lives: My time as the West's top spy inside al-Qaeda

Nine Lives: My time as the West's top spy inside al-Qaeda